According to the Energy and Environmental Institute, residential and commercial buildings are responsible for almost 40% of US carbon dioxide emissions. In the US, buildings use about 40% of the country’s energy for lighting, heating, cooling and appliance operations. Furthermore, production, transport and materials used – such as wood, concrete and steel – account for another 8% of energy use. One-third of this energy is generated from coal-burning power plants.

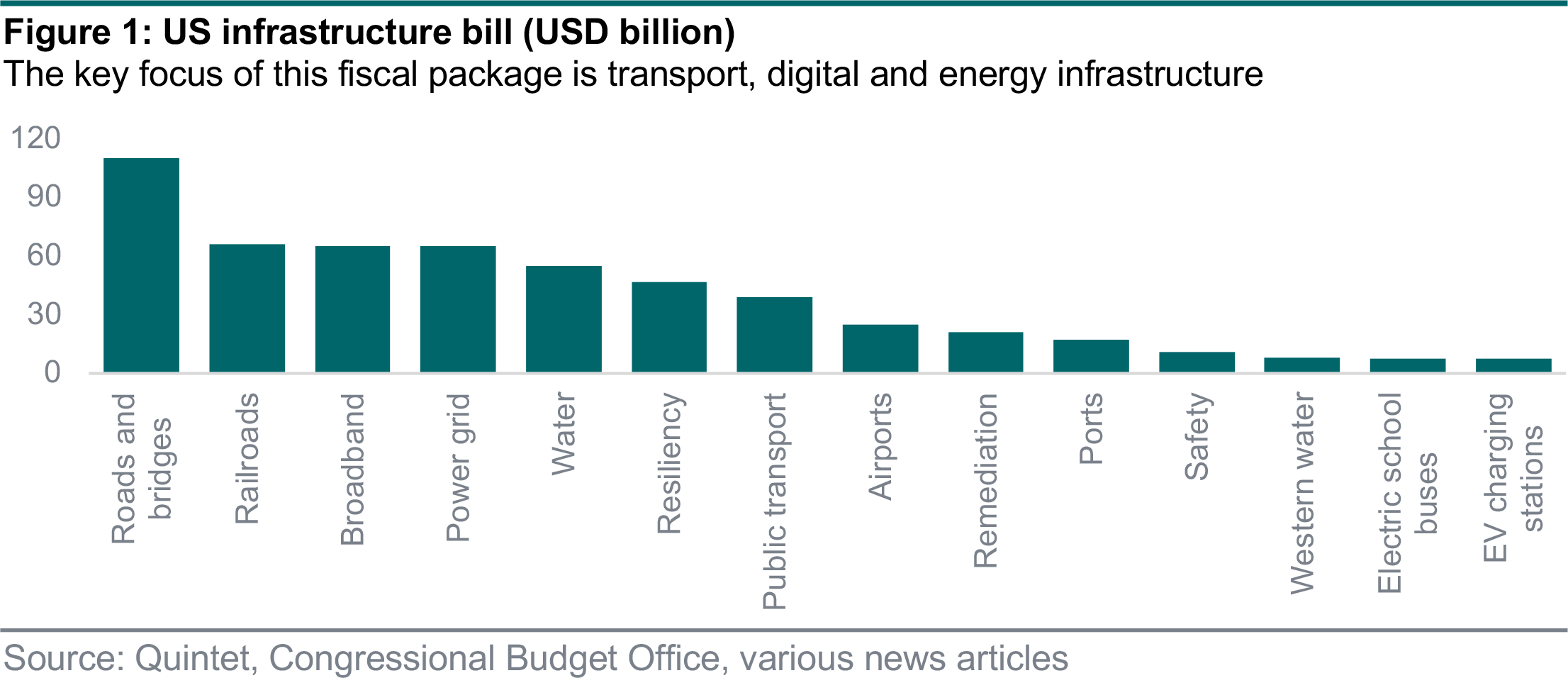

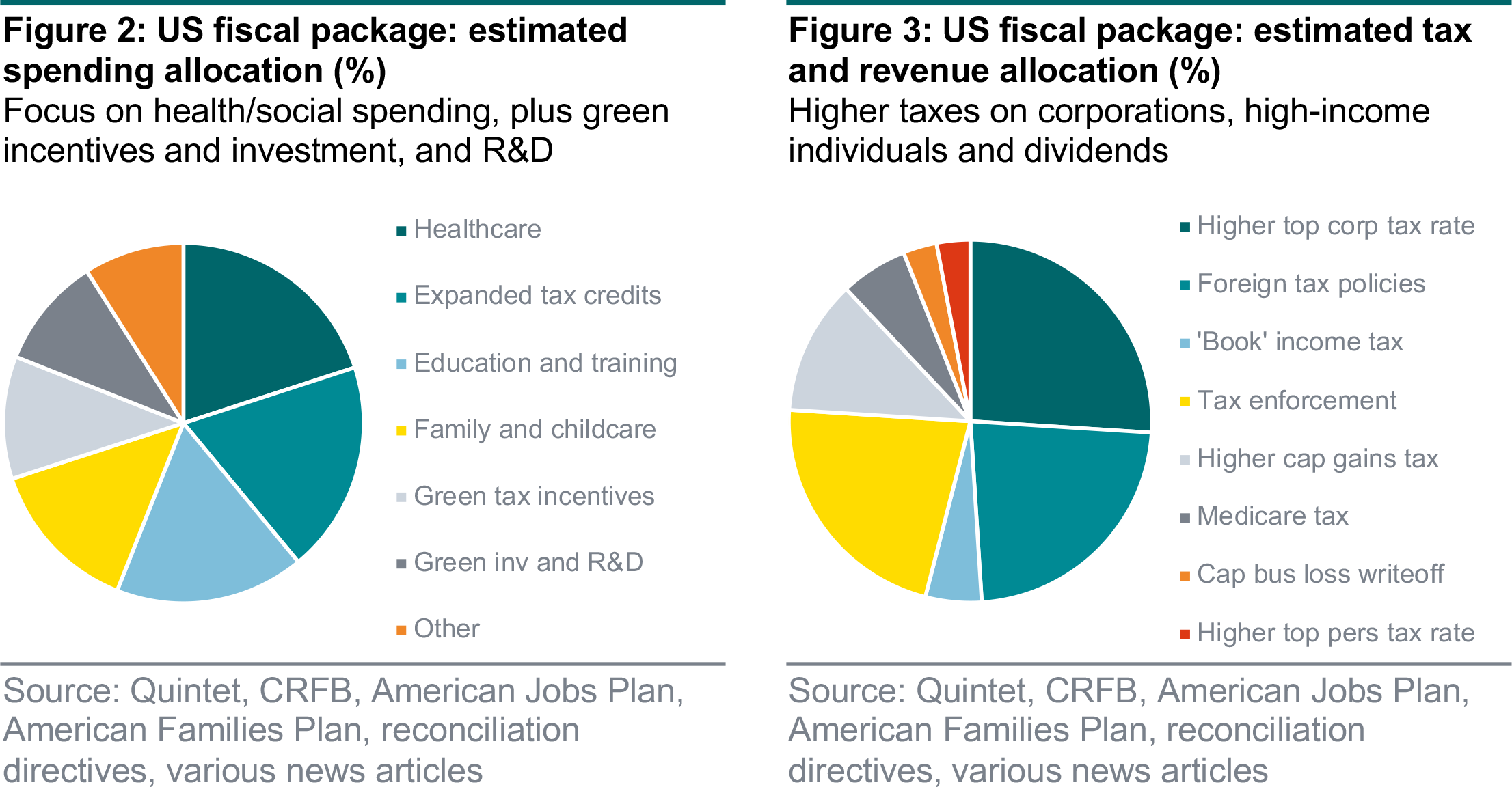

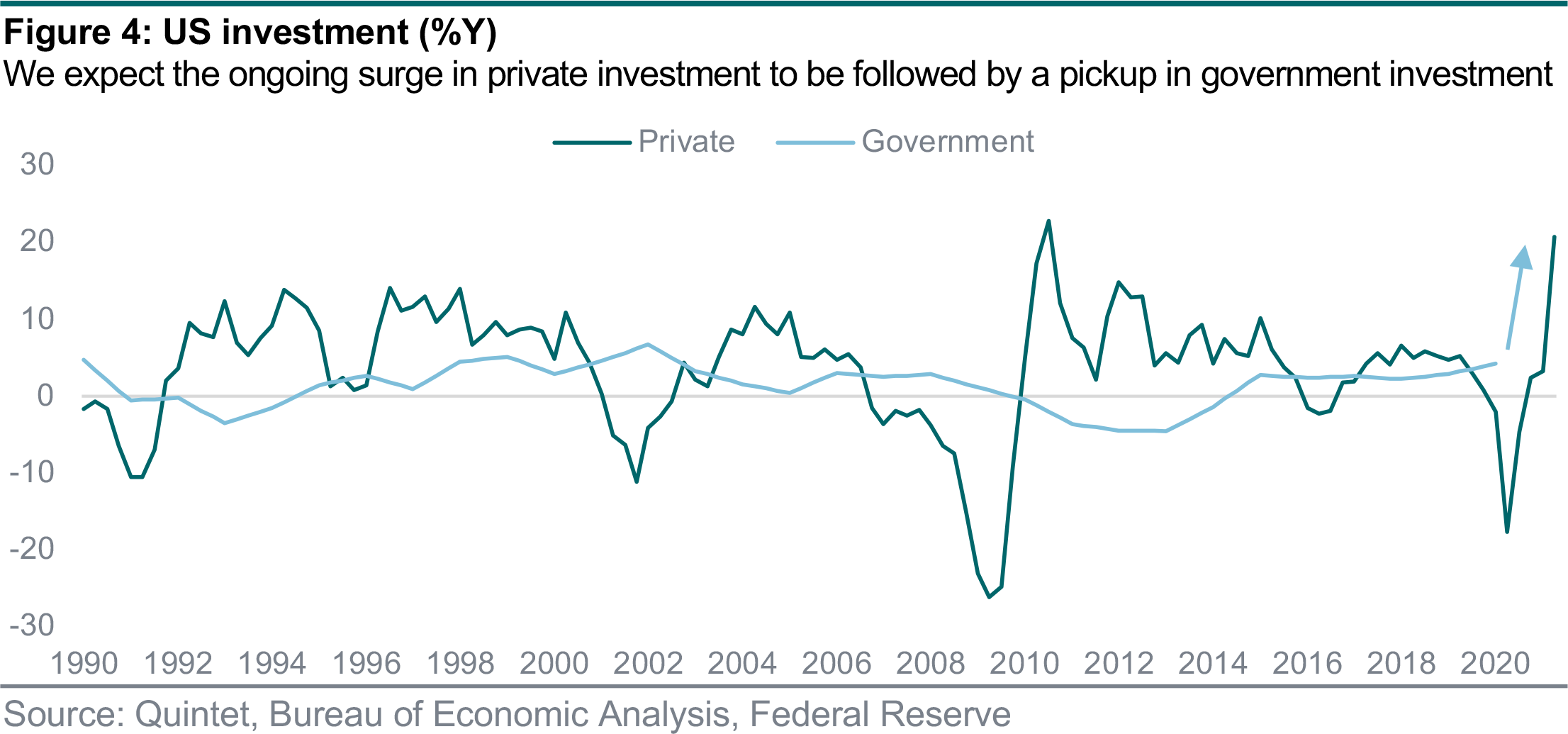

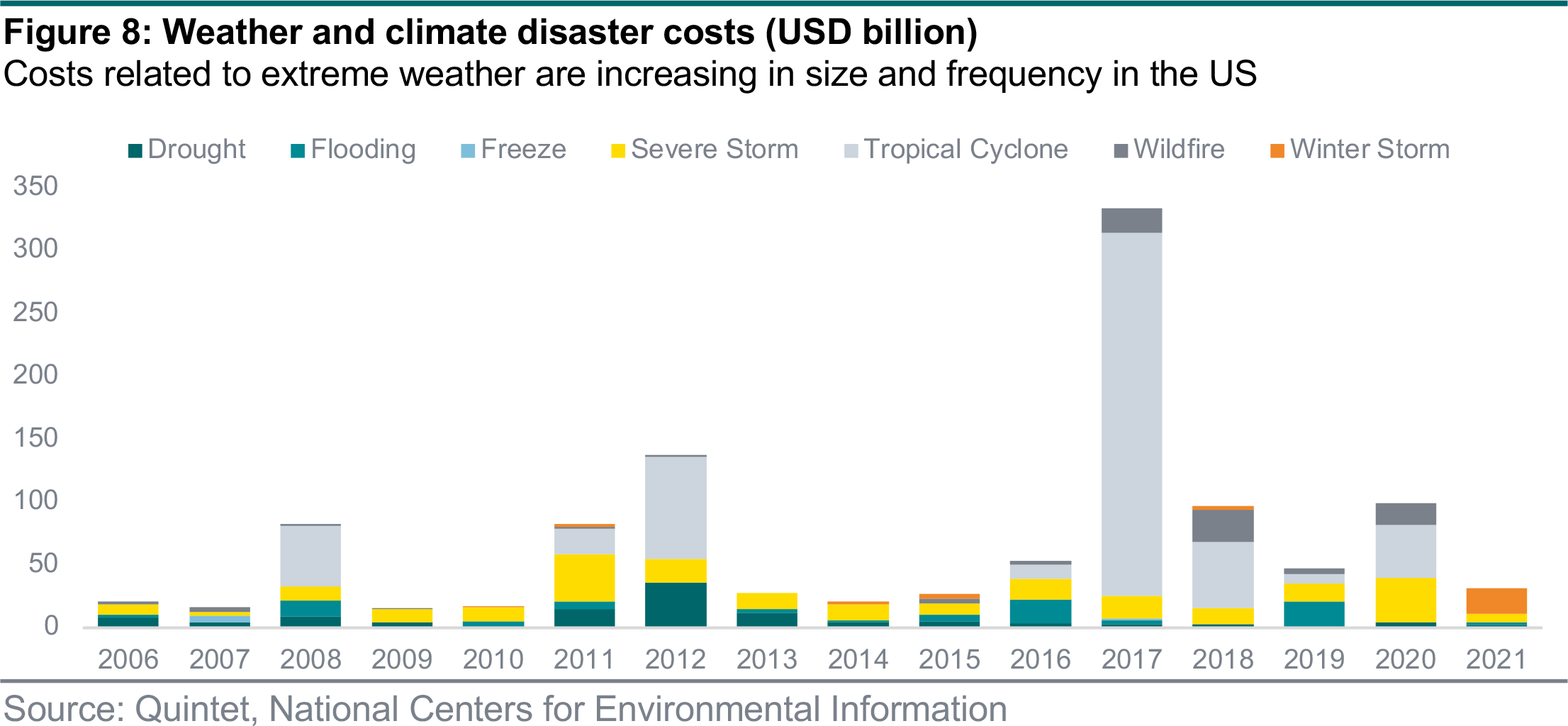

However, infrastructure isn’t just about roads and bridges, but increasingly green and digital investment too. One of the key reasons why we think the push to make infrastructure more modern and sustainable is structural has to do with policymakers’ focus on climate change and human capital.

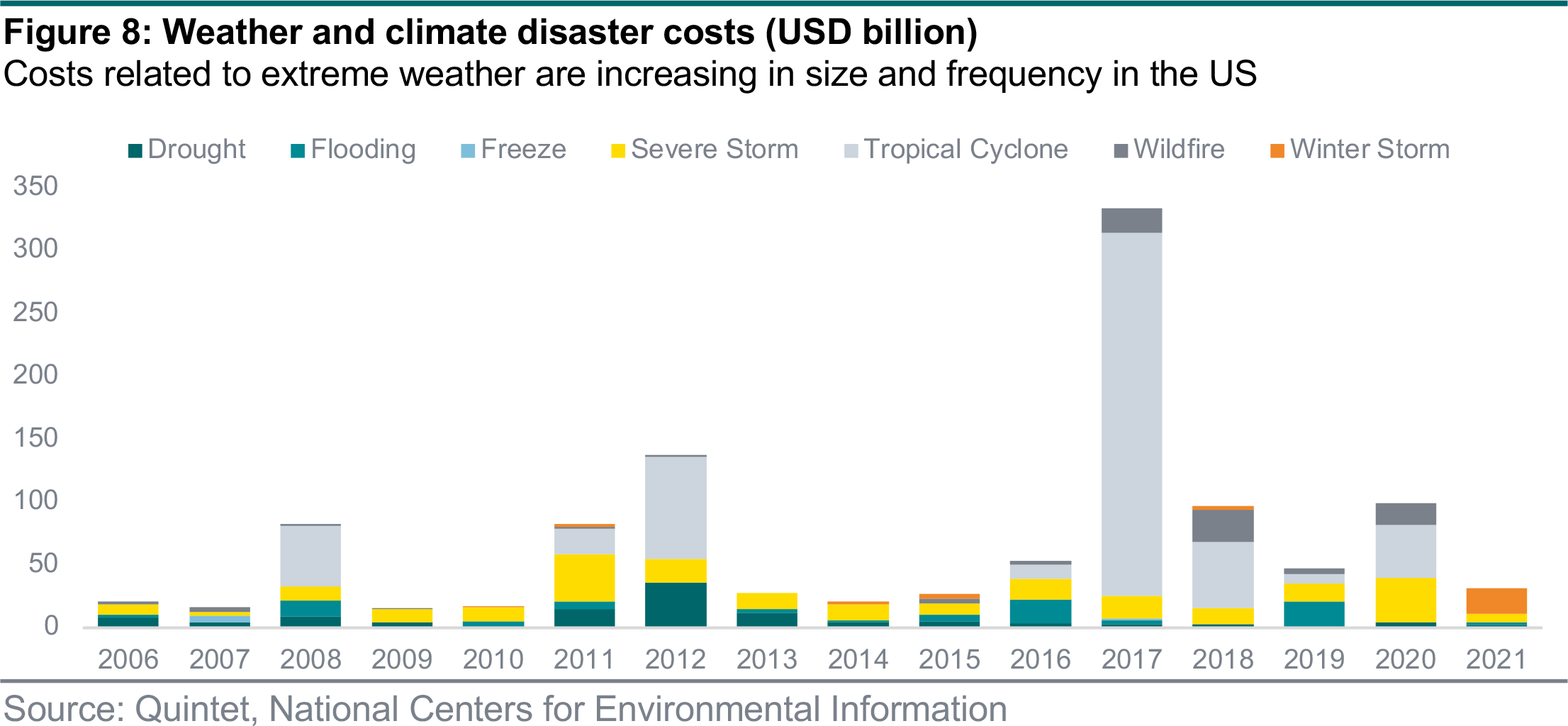

Ways to tackle weather and climate-related disasters – and to reduce their probability of happening

– feature prominently in policy debates. What’s more, water scarcity is a particularly pressing issue. The need to improve the infrastructure to boost human capital, from digital to education, is very much taking centre stage too. Let’s take a look at some examples.

There have been 298 major weather and climate disasters, in the US alone and a quarter of them were in the last five years. According to the US National Centers for Environmental Information, the total cost is in the hundreds of billions (figure 8). The average age of the nation’s dams in the US is 57 years and the US Environmental Protection Agency projects that 4,600 bridges may be at risk from increased rainfall by 2050. The old and now fragile infrastructure had not been built to withstand these extreme weather events and any that may arise over the next several years and decades from large floods and earthquakes. The latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change shows that extreme temperature events that previously occurred once every 10 years are 4.1 times more likely to occur if global warming rises to 1.5ºC above pre-industrial levels.

Water is still scarce in many parts of the US, especially in the southwest where drought is a problem. A report by the EU Commission highlighted how water scarcity affects 11% of the population and 17% of the EU territory. 20–40% of Europe’s available water is being wasted (leaks in the supply system, no water-saving technologies installed, too much unnecessary irrigation, dripping taps and so on). There are innovations that have been developed to fight this, such as waste-water recycling and other waste-saving technologies across commercial, industrial and residential areas, but more needs to be done.

The Federal Communications Commission says that, in 2019, an estimated 14.5 million people in the US didn’t have access to fixed broadband service and 8.4 million to mobile broadband. This is disproportionately affecting low-income earners, especially in rural areas and in those exhibiting higher poverty rates. In the US, broadband service is not a utility (such as water, electricity or gas) – in some Asian countries it’s available to all, at reasonable prices. The broadband providers can charge much higher tariffs to make a profit in these hard-to-reach areas. Broadband availability on tribal lands, in particular, has significantly lagged that of the rest of the country.

Education infrastructure is in dire need of replacement. For example, during the global financial crisis of 2008, capital outlays for schools in the US decreased almost 40% and only returned back to that level in 2018. Schools in poorer areas have buildings that could be a health risk. With the student population increasing, this means that building extensions and equipment upgrades are urgently required, according to the National Center for Education and Statistics. The overall picture is no different in Europe.

Economic policy is increasingly focusing on these areas, with a view to fulfil several broad United Nations’ objectives too. Both the infrastructure bill in the US and the EU green deal will help contribute to multiple UN Sustainable development goals: SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and SDG 13 (Climate Action). In addition, SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation), SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) and SDG 12 (Responsible Production and Consumption) will be positively impacted.

The Horizon 2020 European Green Deal Call looks at both mitigation and adaptation methods to combat the climate crisis and has selected 72 research and innovation projects for funding. These projects help protect Europe’s unique ecosystems and biodiversity, investing in environmentally friendly technologies. The projects funded under this initiative are expected to deliver results with tangible benefits in areas such as clean, affordable and secure energy, the circular economy, energy and resource efficient buildings, and sustainable and smart mobility, just to name a few. This is why we think the intersection between infrastructure and sustainability is a structural trend.