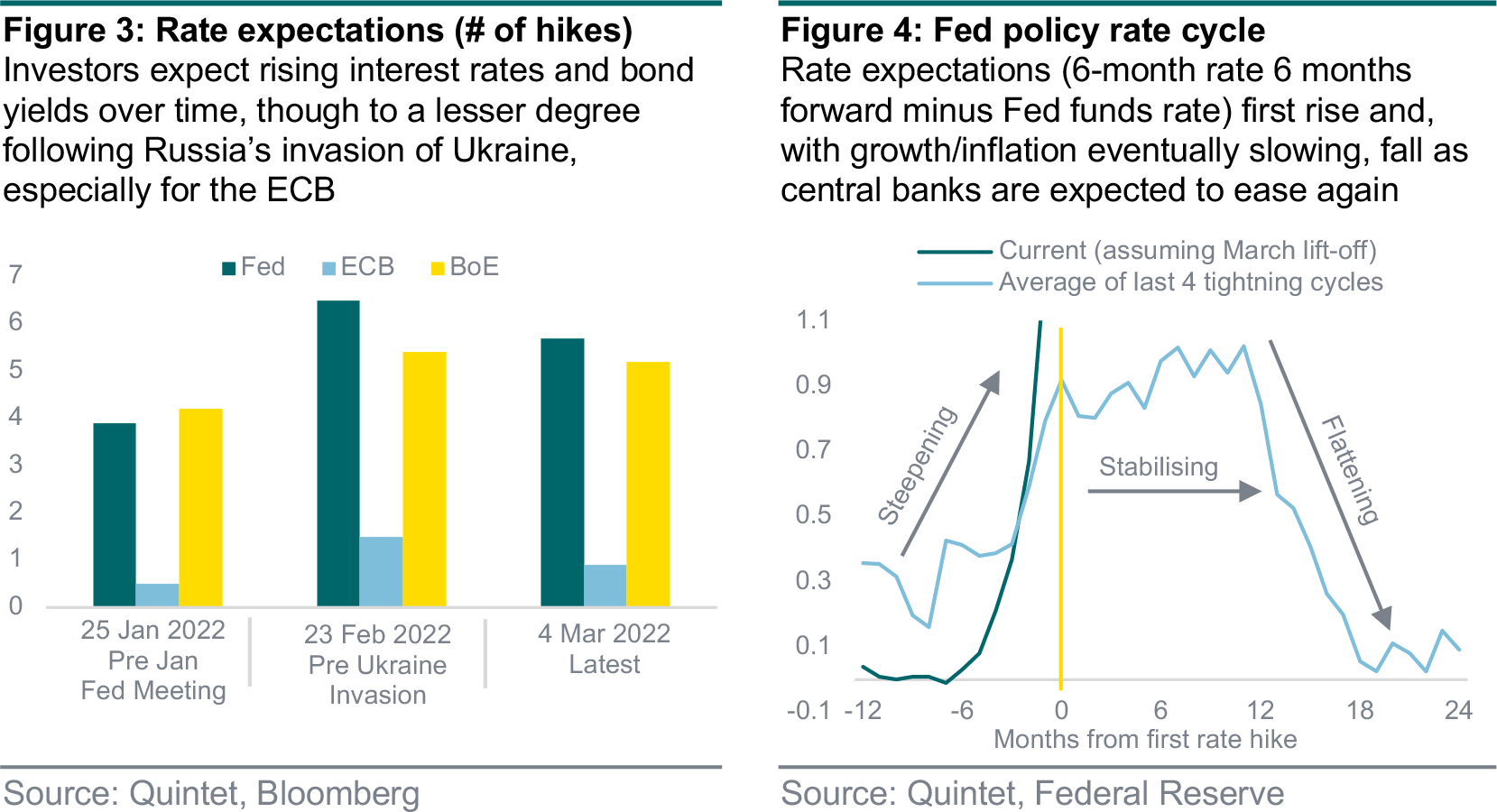

- Our Counterpoint 2022 argues that bond yields, while rising, are likely to stay at relatively low levels. Before the Russia/Ukraine conflict, market expectations were projecting what we considered too many rate hikes. These expectations are now converging to our view, especially for the ECB, which is unlikely to hike rates much above zero in 2022–23.

- We expect the Fed to start, and probably the Bank of England to continue, hiking rates and/or shrinking their balance sheets this month. But, while front-loaded, we suspect the sum of rate hikes in this cycle is likely to be relatively low, to reach 2–2.5% in the US and 1.5% in the UK over the next two years. This should cap the rise of bond yields across the board.

- While geopolitics could increase volatility further, our macro and interest rate view suggests that equity market worries about high bond yields are probably overdone. Credit spreads too reacted to central bank shifts in policy. But they should tighten over the medium term, given solid company fundamentals and positive technicals, even if it’s likely to be a bumpy ride.

Since the turn of the year, market volatility has risen, not least in fixed income markets. It’s tempting to attribute all this to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Of course, geopolitical uncertainty isn’t helping. But the main thing for markets is that central banks and governments are now scaling back their emergency-level support – or are about to. This is because economies have recovered a great deal. And, while we still think policy normalisation, growth moving past the peak and supply-chain repair should all contribute to subsiding inflation over time, inflationary pressures remain high for now. We always thought that markets were pricing too many rate hikes and more than warranted, given our outlook. We now see rate expectations converging towards our more dovish scenario.

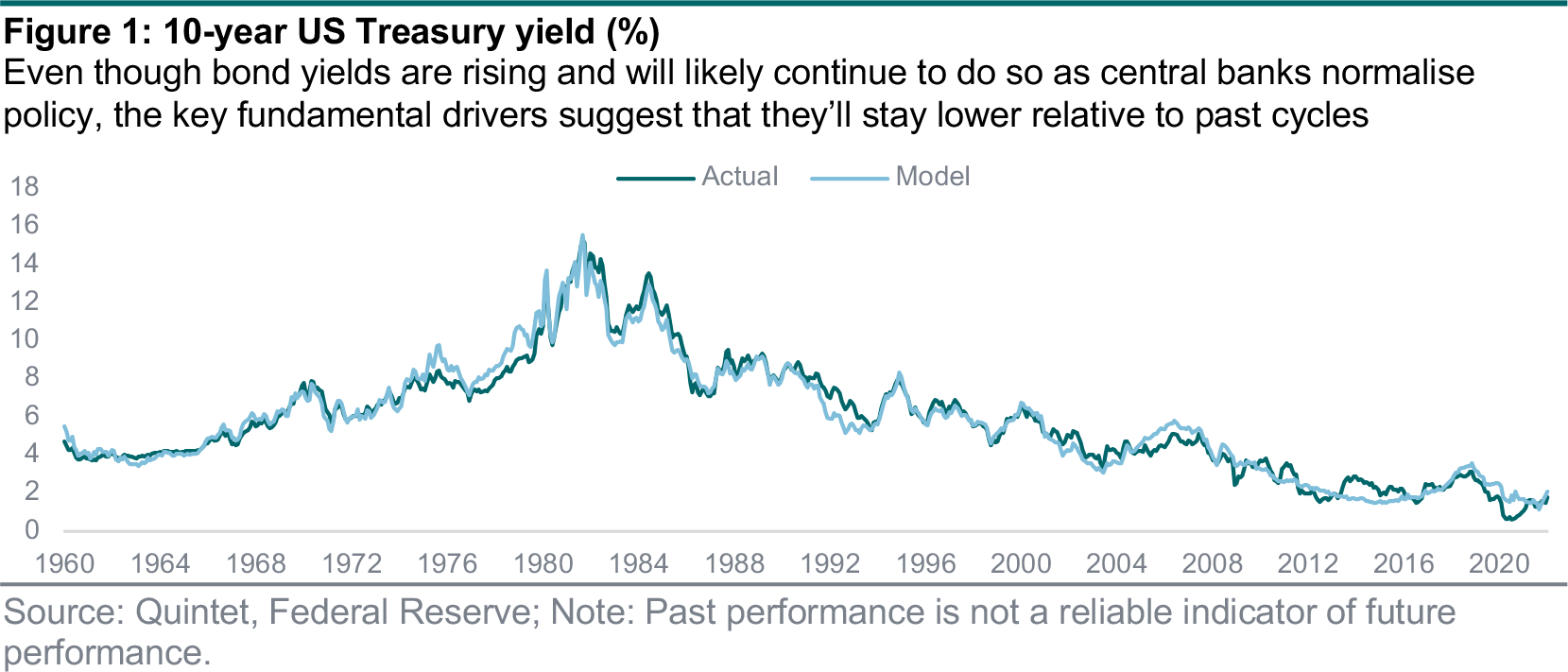

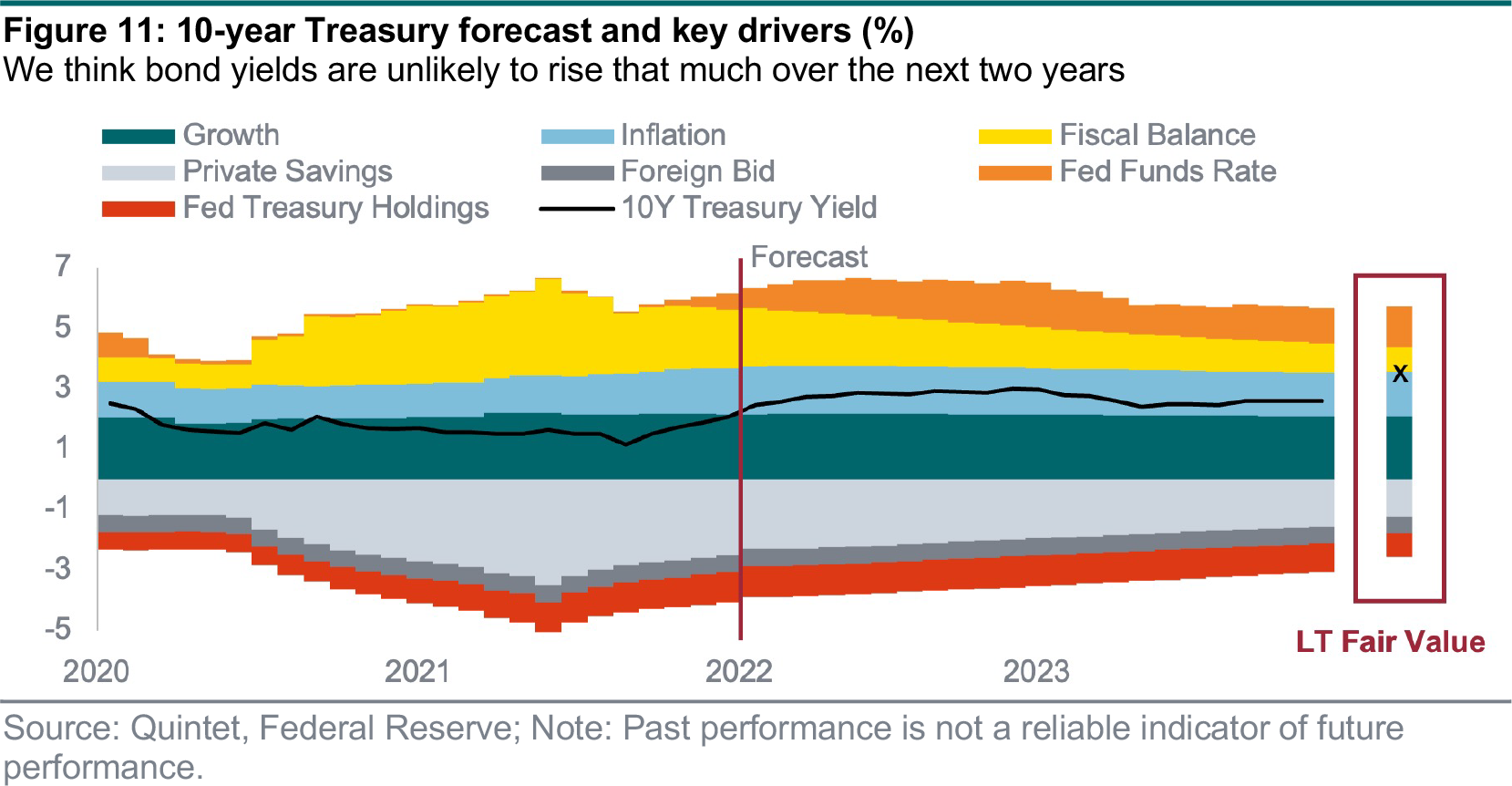

Our new interest rate model projects bond yields based on growth and inflation, monetary and fiscal policy, and the balances of households, corporates and foreigners. It points to higher, but by no means high, bond yields, with the 10-year Treasury reaching just over 2.5% at the end of our detailed forecast horizon (2022–23). We also incorporate the typical behaviour of market expectations, which tend to anticipate the hiking cycle (initially raising bond yields) and its impact on growth/inflation later on (subsequently lowering them). This creates a ‘hump’ in the yield path, resulting in a temporary overshoot, possibly to 3% or so in 12 months. But while 3% could be a reasonable long-term fair value, anything causing extra risk aversion – including the Russia/Ukraine situation – could depress bond yields, so we don’t see yields rising that much in the short term.

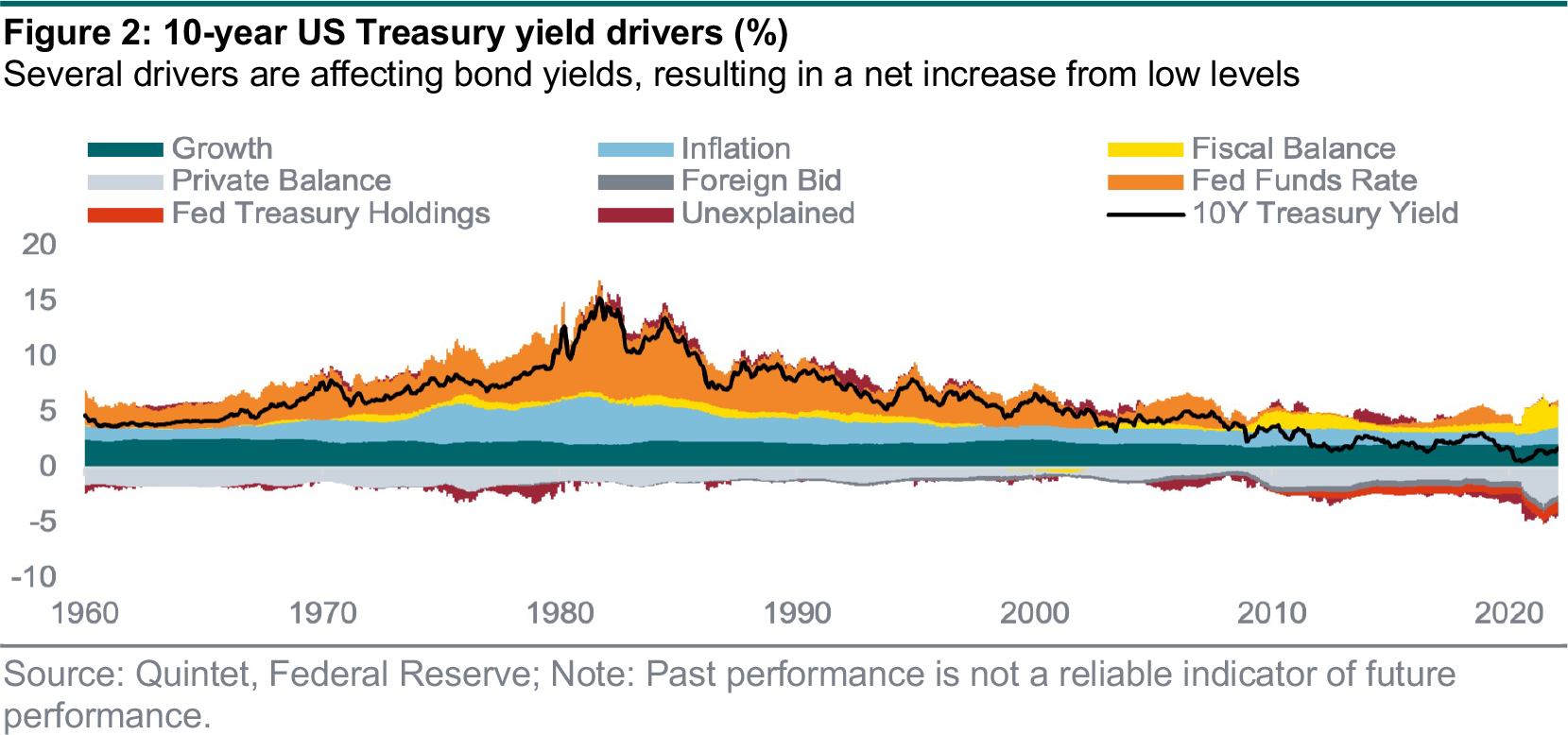

The long-term decline in bond yields – since the 1980s – has ended. This means higher yields relative to the decade before the pandemic, when balance-sheet repair and fiscal austerity depressed growth and inflation, but not high yields in an absolute sense. While moving past the peak, the economy is growing above trend. Supply disruptions, coupled with reopening demand, are raising inflation, which should nevertheless decline from high levels as things settle down. Monetary policy normalisation should lift bond yields (figure 2). Our outlook is more dovish than market pricing, which has started to converge to ours. We think central banks will likely continue to monetise debt to finance fiscal stimulus and cushion energy/supply shocks (e.g., related to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine) as warranted.

In our model, monetary policy affects bond yields in three distinct ways. First, all else being equal, a percentage point increase in the Fed funds rate would lift the 10-year yield by a little over 50 bps.

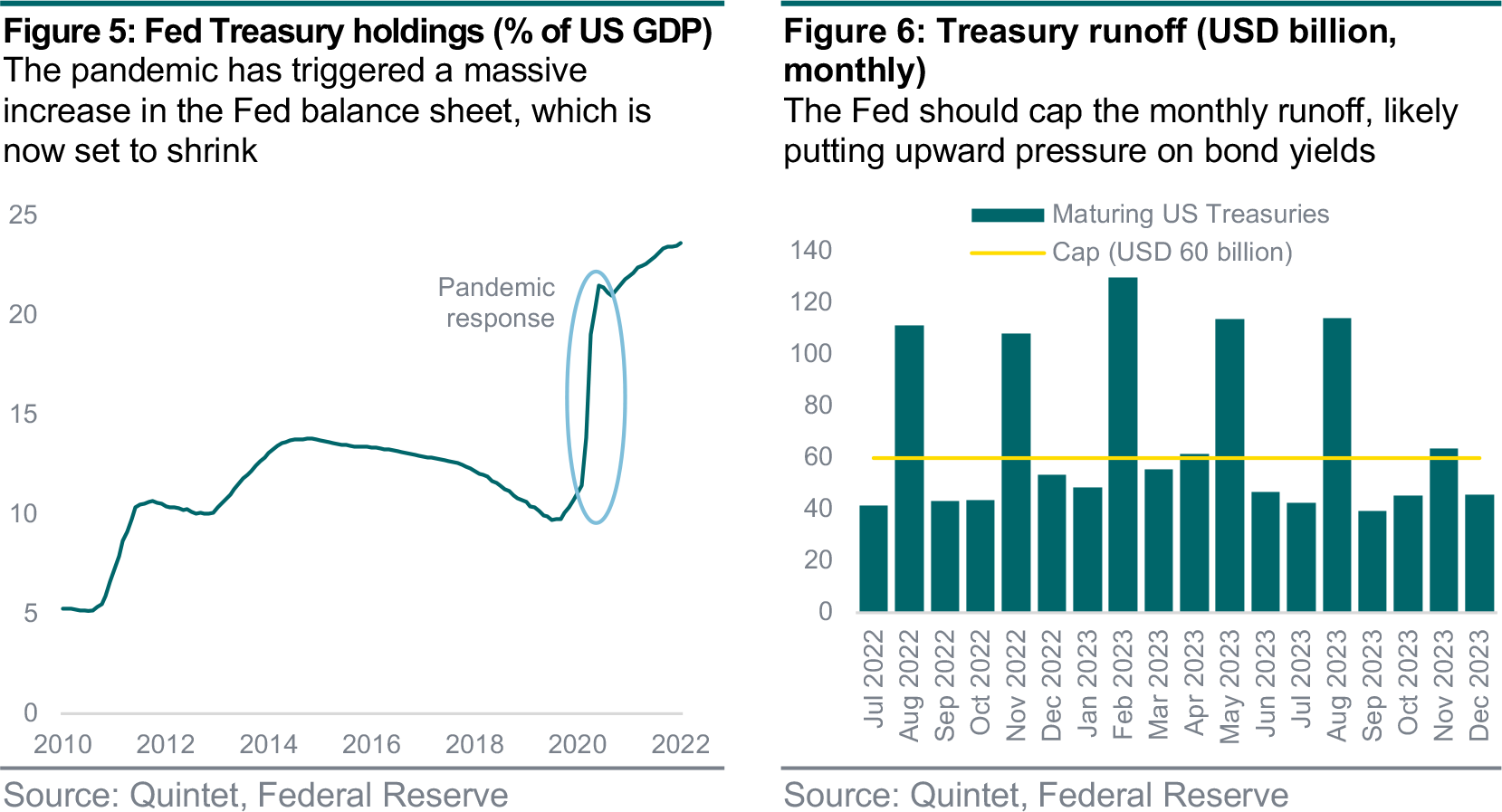

As we expect the Fed to hike five times in 2022 (in line with market expectations, which have now converged to our view), this would imply a roughly 65 bps yield increase (figure 3). The second channel is via the Fed’s forward guidance. By setting out its reaction function, the central bank can guide market expectations. Past cycles have shown that, on average, the bulk of the market reaction happens in the six months leading up to the first rate hike (figure 4). As we expect the Fed to start hiking this month (March), this would imply only a moderate boost to yields going forward, before the effect stabilises and ultimately fades in 2023, creating a hump-like trajectory.

The third transmission channel for monetary policy is via the Fed’s balance sheet (figure 5). In response to the pandemic, the Fed bought vast amounts of Treasuries to keep financing costs affordable, so that the Federal government could spend unprecedented sums. With the US economy faring better and no longer in need of ultra-accommodative policies, and above-target inflation, the Fed has announced a passive unwind of its balance sheet (i.e., not reinvesting maturing bonds), which has increased to close to USD 9 trillion. To illustrate this point, assuming a monthly reinvestment cap of USD 60 billion (figure 6), this should put some moderate upward pressure to bond yields. Of course, any event causing uncertainty and, therefore, an extra bid for safe-haven assets, such as the Russia/Ukraine situation, could support the Treasury market and keep yields lower than these model-based projections imply.

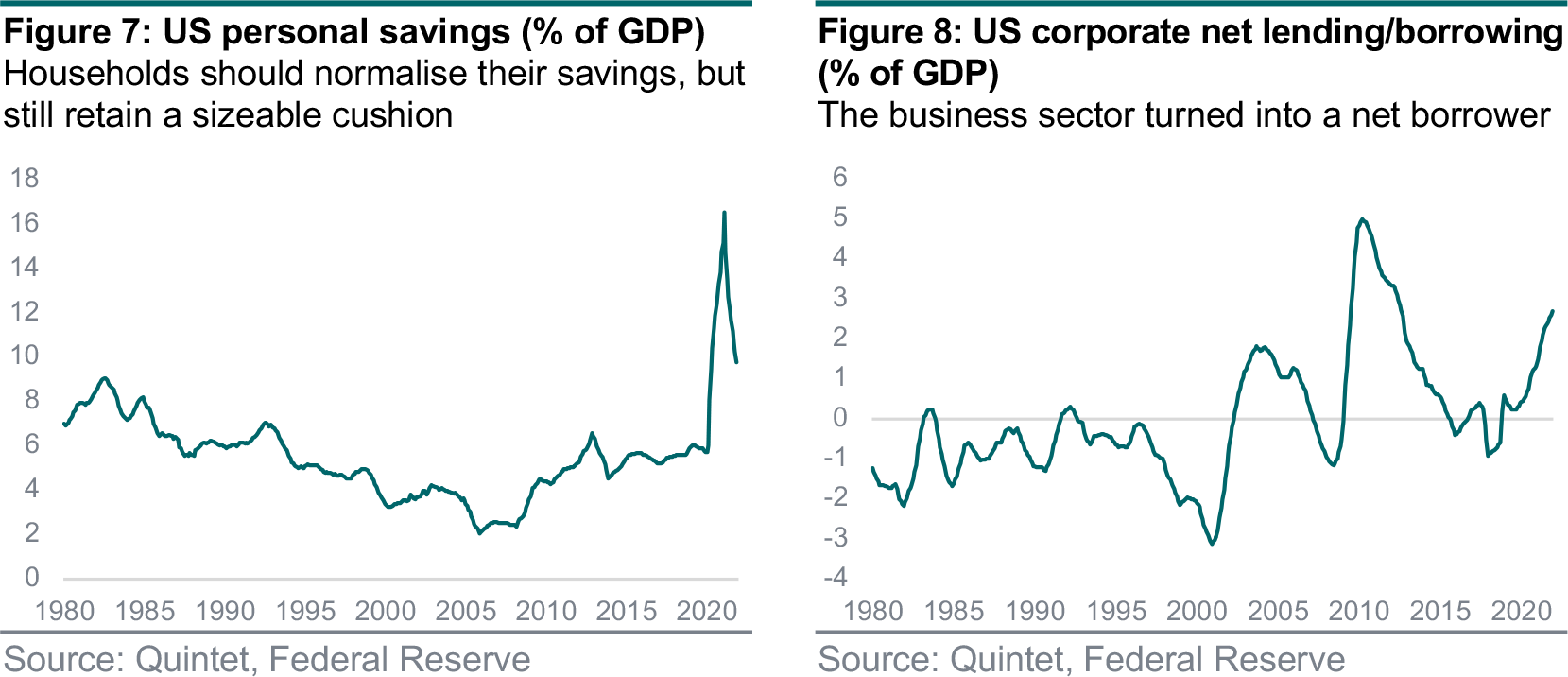

The Fed is not the only one with a sizeable balance sheet. Household savings rose significantly during the pandemic, given a fiscal boost to incomes, limited spending opportunities during lockdowns and the need to build a precautionary cushion (figure 7). This led to surging demand for Treasuries, further suppressing bond yields. As these savings are being spent, and with no extra stimulus cheques coming through, this should now put some upward pressure on yields. However, we’d still expect relatively larger buffers of reserves – as uncertainty remains – which should anchor bond yields at low levels. Similarly, reduced corporate savings should lead to higher yields, though we think this effect too is likely to be small. Overall, private savings should continue to pull bond yields downwards – just less so (figure 8).

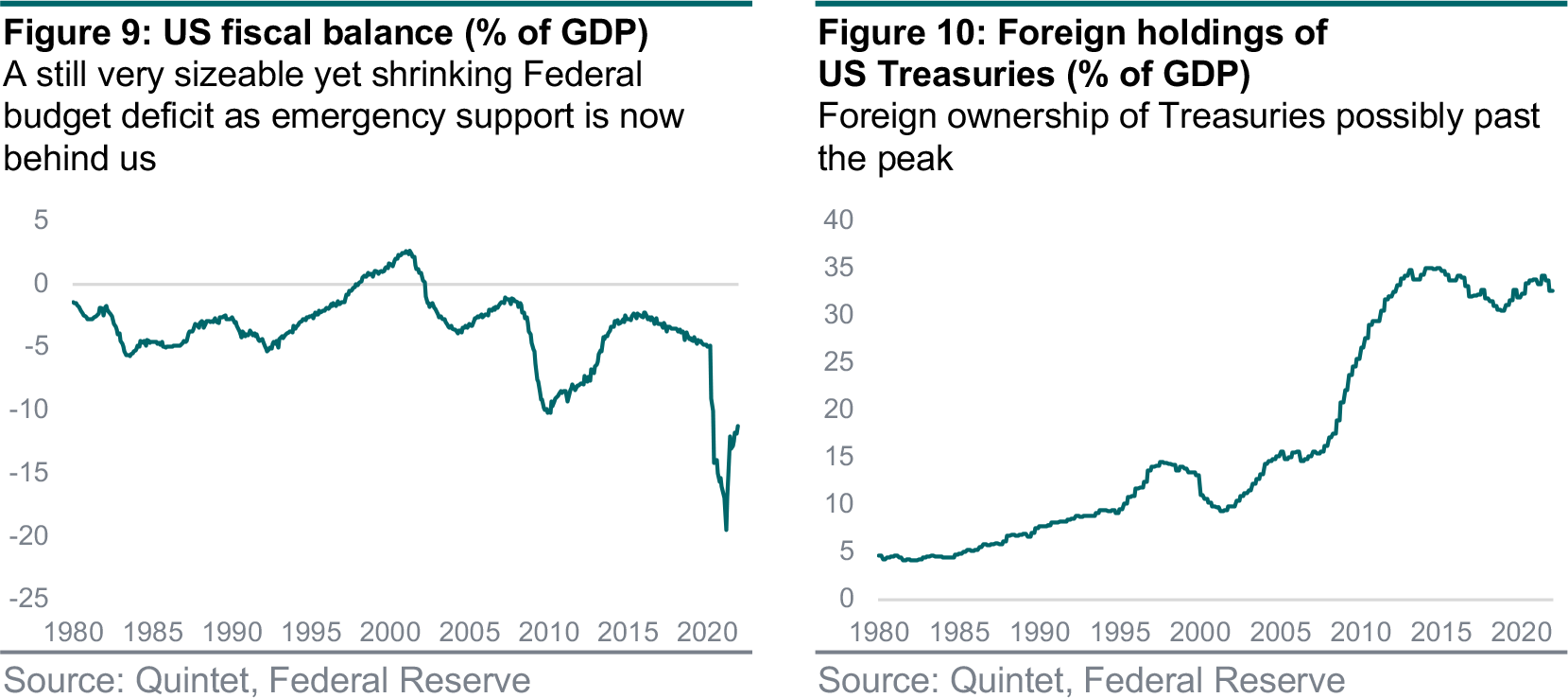

The Federal budget deficit plummeted in 2020–21, as the US government enacted various measures to cushion the economic fallout of the pandemic (figure 9). To finance them, Treasury supply was ramped up, putting upward pressure on bond yields. The fiscal impulse is fading quickly, however, with falling bond issuance acting as a break on rising yields. While some of the increase in supply was absorbed by domestic investors sitting on vast amounts of savings, the foreign bid also increased, given the relative yield advantage of Treasuries over European and Japanese government bonds (figure 10). In this case too, geopolitical uncertainty related to Russia/Ukraine may have some impact. After all, US Treasuries are the quintessential risk-free asset. But, further out, we assume that foreign buying will slow somewhat.

Our assumptions for Treasury supply and the various sources of demand, plus our macro forecasts, allow us to estimate the 10-year bond yield path and a long-term fair value. We project eight 25 bps rate hikes until end-2023, plus balance-sheet reduction. Growth should stay solid, while normalising from super-strong rates. Inflation is likely to decline from high levels, though it will probably exceed the low levels of the decade before Covid-19. Normalising private sector savings pushing yields higher should offset smaller government financing needs. Market expectations for the policy rate show the typical hump, potentially pushing the 10-year yield to about 3% (a reasonable fair value over the longer term, and still a low level), before settling down to 2.6% at the end of next year. Given geopolitical uncertainty, we suspect that expectations, while correcting, remain too elevated (figure 11).

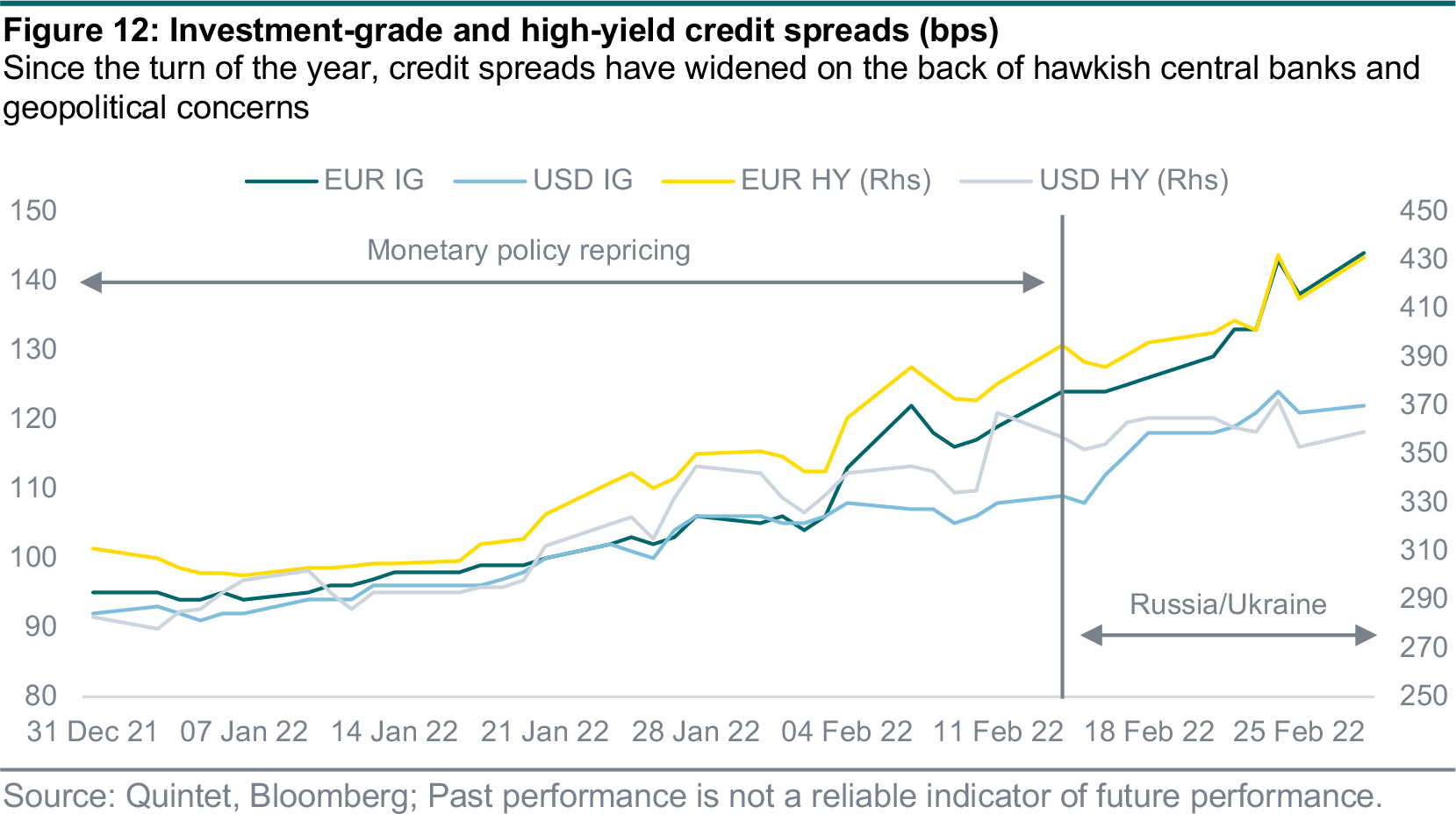

Year-to-date, spread movements can be split into two distinct periods (figure 12). Up until the first half of February, hawkish shifts by several central banks including the Fed and the ECB led to a repricing of rate hike expectations in markets, with credit spreads widening too. This was followed by a period dominated by concerns over the fallout from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Both investment-grade and high-yield bonds have subsequently seen their spreads rise above their respective five-year averages. Based on solid company fundamentals, positive technicals and a likely limited impact going forward, we see room for credit spreads to tighten in the medium term.

Both the Fed and the ECB have highlighted the uncertainty surrounding the potential ramifications of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. While persistently high inflation prints – possibly to be pushed even higher by spiking oil and gas prices – will warrant a policy response in coming months, central banks may tread more carefully than anticipated only a few weeks ago. This could mean a slower pace of tightening, or a delay, particularly for the ECB. We still expect the Fed to confirm a 25 bps hike later this month.

The exposure of both USD and EUR credit to Russia and Ukraine is relatively limited, both in terms of issuer weights in the respective indices and when taking into account operations/assets in the region (figures 13 and 14 on page 6). The most likely channel of contagion will be via the energy sector. On a regional basis, Europe is more exposed in that regard, given its reliance on Russian oil and gas, which account for roughly 30–40% of the region’s total oil and gas imports. Having said that, any significant drag on growth caused by a persistent energy shock may also prompt a strong fiscal response to help households and companies cushion the blow (and/or less monetary tightening).

On a fundamental level, corporate balance sheets are in solid shape, with companies having used years of attractive financing conditions to reduce leverage. This puts them on a healthier footing to weather any potential fallout from geopolitical tensions. Another aspect in favour of tighter credit spreads is shifts in demand vs supply. Issuance has already fallen and, in light of elevated cash buffers, refinancing needs may be lower than expected in coming months.

Overall, we believe that, while the recent repricing is justified in light of a broader shift in market sentiment, credit spreads have room to tighten from here, even if it’s likely to be a bumpy ride.

There are three broad macro risks to our base case. First, to the downside, growth could slow more significantly, either because rising oil/gas/commodity prices take a toll or because of a ‘policy mistake’ (central banks tightening too much, too fast). Second, to the upside, more monetary/fiscal support could strengthen borrowers’ creditworthiness. Third, the situation in Russia/Ukraine and the West’s response could evolve differently, either escalating or de-escalating, and impact financial conditions – and hence the Fed’s reaction – positively or negatively.

Fed funds rates have limited directional impact on credit spreads, which depend on overall economic health, corporate credit fundamentals and financial stability/stress. But, while the impact of asset purchases on Treasuries has been diminishing, much of the excess liquidity has been going into credit. US high-yield credit spreads are significantly lower this time around than at the start of any prior Fed tightening cycle. So, if the Fed were to shrink its balance sheet more rapidly than warranted, one risk is that spreads could widen.

Our investment experts share their views on financial markets and investing, as well as the themes we think will drive tomorrow’s economy – from sustainability issues and the fight to mitigate climate change to the ongoing digitalisation of many aspects of our lives.

Authors:

- Daniele Antonucci Chief Economist & Macro Strategist

- Bernhard Eschweiler Consultant

- Tom Kremer Senior Macro Strategist

- Lionel Balle Head of Fixed Income Strategy

- Bill Street Group Chief Investment Officer

This document has been prepared by Quintet Private Bank (Europe) S.A. The statements and views expressed in this document – based upon information from sources believed to be reliable – are those of Quintet Private Bank (Europe) S.A. as of 7 March 2022, and are subject to change. This document is of a general nature and does not constitute legal, accounting, tax or investment advice. All investors should keep in mind that past performance is no indication of future performance, and that the value of investments may go up or down. Changes in exchange rates may also cause the value of underlying investments to go up or down.

Copyright © Quintet Private Bank (Europe) S.A. 2022. All rights reserved.